| SOLSTICE: An Electronic Journal of Geography and Mathematics Persistent

URL: http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/58219

|

|

Works best with a high speed internet connection.

| SOLSTICE: An Electronic Journal of Geography and Mathematics Persistent

URL: http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/58219

|

|

June, 2012 |

|

Geosocial

Networking: A Case from Ann Arbor, Michigan

David E. Arlinghaus and Sandra L. Arlinghaus Associated .kmz download.  Social networking is

an idea that is familiar to many of us: from Facebook, to Twitter, to

LinkedIn, to a host of others that come and go. More recent,

however, is the idea of "geosocial networking" or "collaborative

mapping." According to Wikipedia (2012),

"Geosocial

Networking is a type of social networking

in which geographic services and capabilities such as geocoding

and geotagging are used to enable additional social

dynamics.[1][2]

User-submitted location data or geolocation

techniques can allow social networks to connect and coordinate users

with local people or events that match their interests. Geolocation on

web-based social network

services can be IP-based or use hotspot trilateration.

For mobile social networks, texted location information or mobile phone tracking can enable location-based services to enrich

social networking."

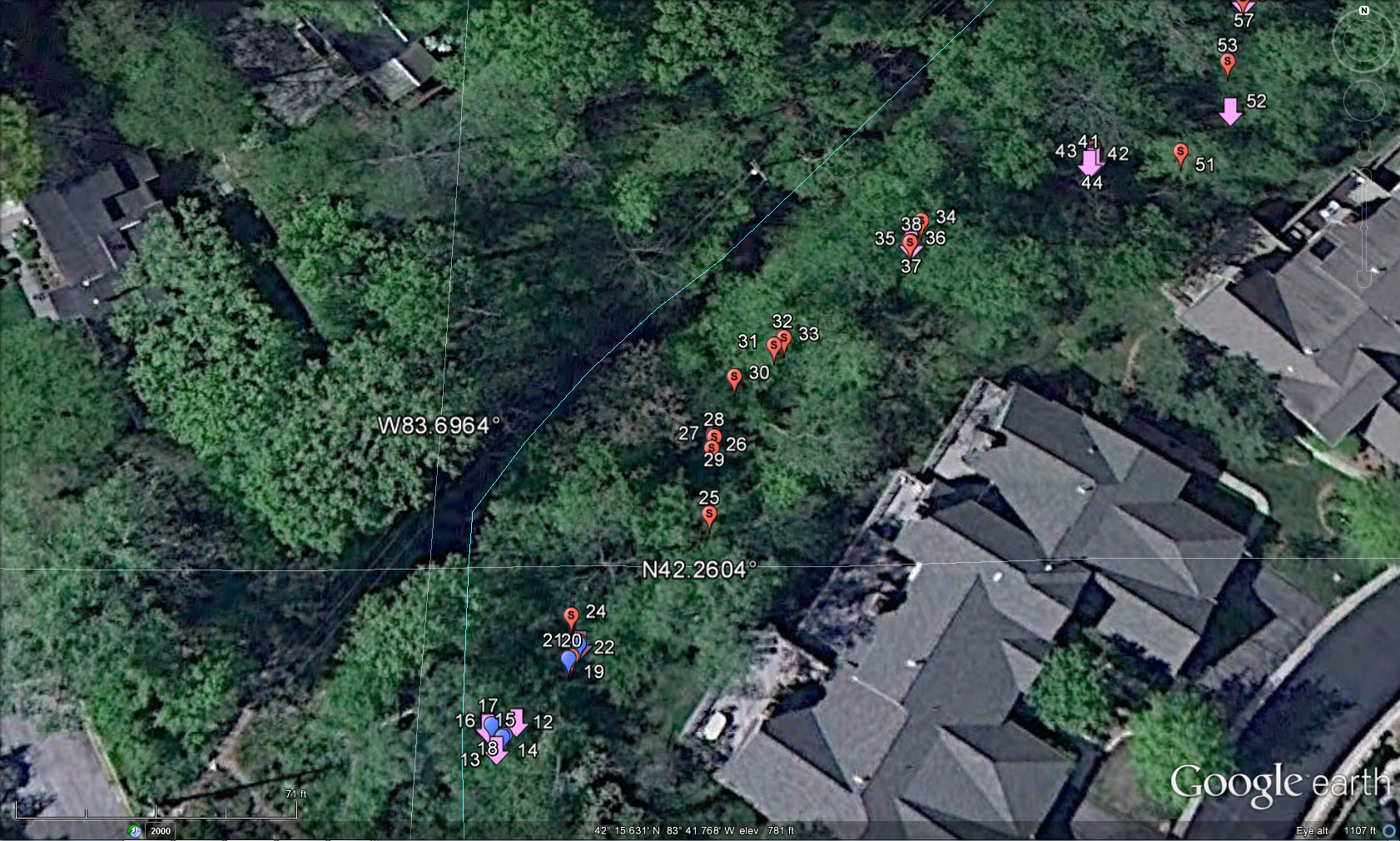

Recently, Washtenaw County, Michigan embarked on a

major stream bank erosion control project. When

that project entered heavily forested

residential lands adjacent to

a creek, environmentally-sensitive residents quite naturally became

concerned

for the trees and wildlife that will be destroyed or disturbed. The project is still on-going and the geosocial

network described below remains in place. The County coded its easement with pink flags. It tagged selected large trees or otherwise

interesting vegetation with a blue band if they were to be removed; it

tagged

trees within the easement with a red band if they were to be left alone. All vegetation within the easement, except

trees or shrubs carrying red tags, were to be removed.

Color was critical—a simple red/blue

confusion could cost a tree its life! One

neighborhood used Google Earth, together with a

GPS-enabled smartphone, to make an inventory of trees present, along a

half-mile stretch of the creek, before the project began. David

E. Arlinghaus did all the photography

with a smartphone that geotagged the images.

He then transmitted the images to Sandra L. Arlinghaus who did the

mapping using a combination of GeoSetter and Google Earth

(Figure 1).

|

| The

accuracy of the geotagging of the photos was limited by

several factors. First, the software in

the smartphone has limits. Second, the

geotagging of the tree is actually the geotagging of where David stood

to take

the picture of the tree, rather than of the tree position,

itself. He attempted to stand at a consistent

distance from trees to ensure precision (but that is difficult in a

densely

wooded area). The level of precision,

however, was quite good—trees were in correct relation to each other

and in

close to correct relation to dwelling units.

The geotagged camera images were downloaded directly

to a

computer by plugging the smartphone into a recent Windows 7 desktop

computer. All 81 images were stored in a

single

folder. That folder was then uploaded to

the free software called “GeoSetter.” From

there, the geotagged images were batch-uploaded

to Google Earth in

a single operation (rather than entering each one individually). The GeoSetter software was able to take the

underlying geocoded coordinates from the camera images, as well as the

images

themselves, and make them correspond to the underlying coordinate

geometry in

Google Earth. We made color decisions to

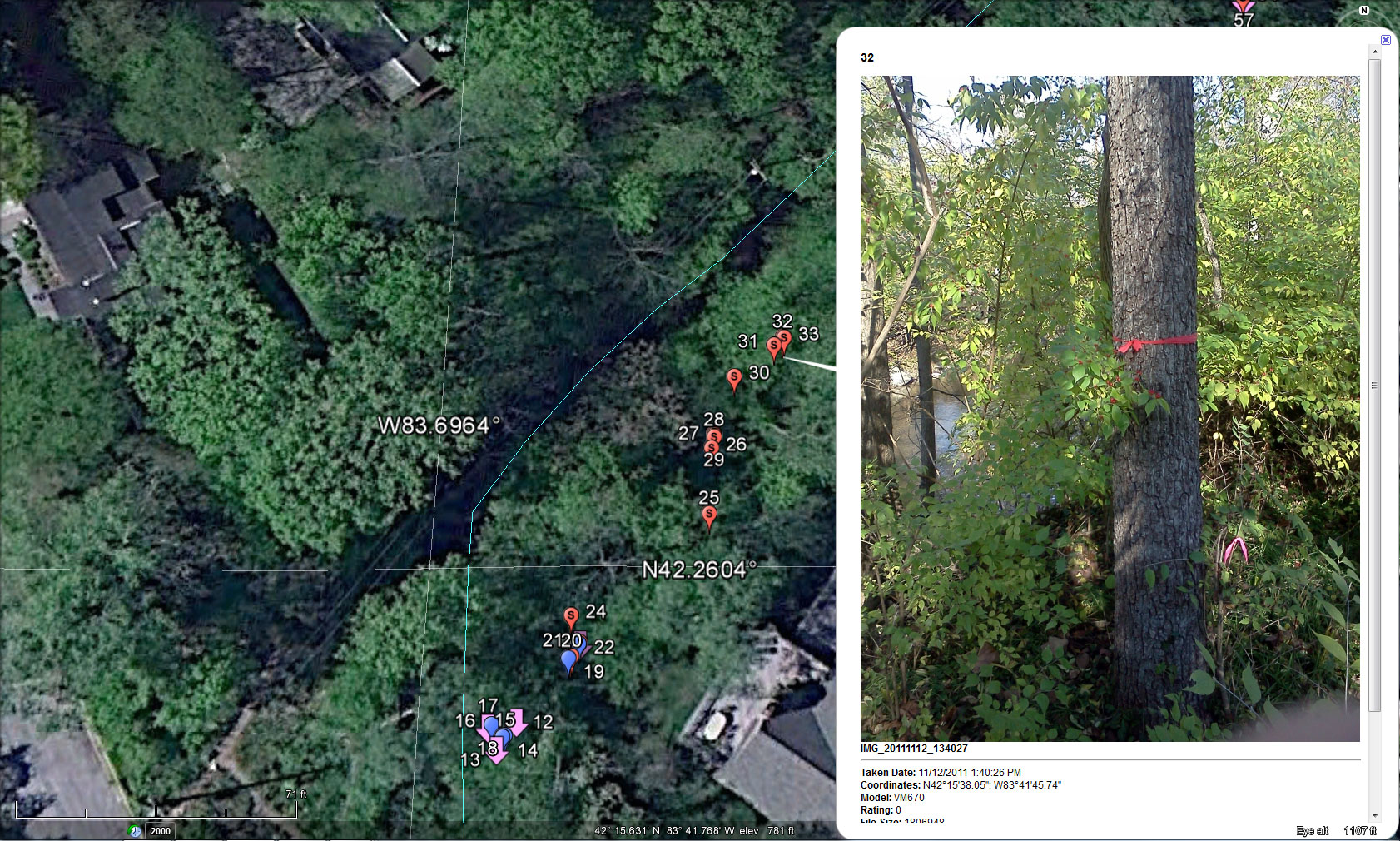

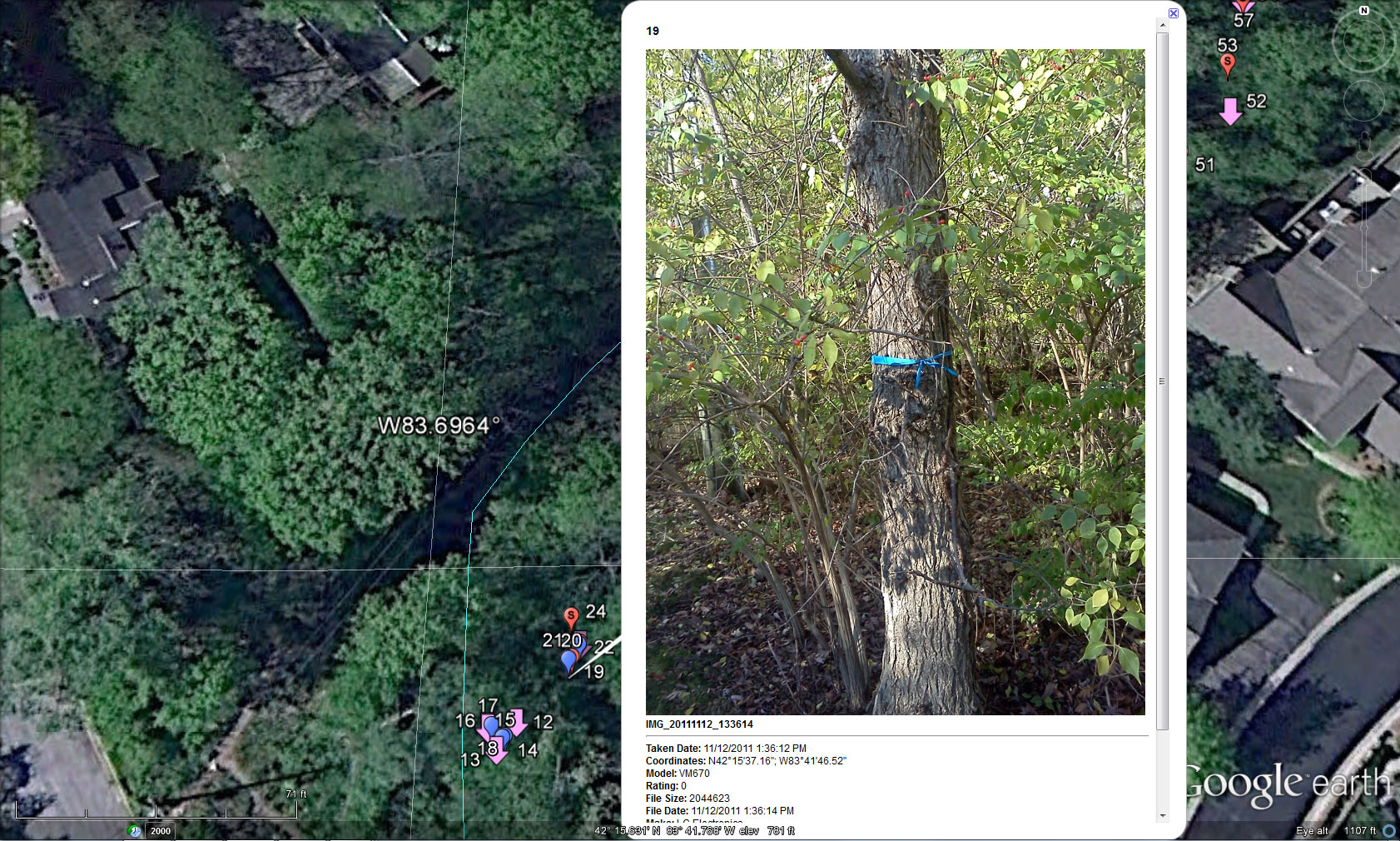

correspond with the actual colors of tags used on vegetation. Accuracy, of registration of photo and Google Earth coordinates, using this sort of strategy was guaranteed. Hand placement would not offer that level of accuracy of registration. Overall, the results were sufficiently precise (although not accurate) to offer local residents a clear picture of what was going to happen in wooded areas. When the camera GPS coordinates were obtained, a photo of the tagged item was also taken. Figure 2 shows a photo displayed on the Google Earth surface pointing to the identified red-tagged tree. Figure 3 shows a similar configuration of photo in relation to Google Earth base pointing to the identified blue-tagged tree. These pointing associations are all accurate. Download the linked .kmz file, open it in Google Earth, and you will see associations of this sort for all 81 trees marked by the County before the time of photographing. |

| The

neighborhood association established a tree

monitoring

committee. The committee was given

a Google Earth file showing tree location and associated tag

color.

The easement was also geocoded. Prior to using the file, the

neighborhood

association president and the creator of the

Google Earth display met with the lead County official and the lead

engineer on the project to ensure a cooperative approach to file

usage.

Subsequently, the tree monitoring committee used the information in

conjunction with field-checking vegetation. Geosocial networking

was, and is (through remaining tree restoration scheduled in late fall

2012),

critical in developing a

constructive relationship among the various parties adjacent to this

well-meant and successful evironmental stream-bank restoration project.

References

Numerous people were involved directly and indirectly in this project that brought together County and City officials, Engineers from a local engineering firm, and members of the public from a variety of neighborhoods including differing residential types and zoning. We thank: Harry Sheehan, Greg Marker, Jane Lumm, Roger Rayle, Janice Bobrin, Matt Naud, and all the member neighborhoods of the Huron Valley Neighborhood Alliance and the individuals from those neighborhoods who participated in so many helpful ways. |

|

|||

| 1.

ARCHIVE 2. Editorial Board, Advice to Authors, Mission Statement 3. Awards

|

|

.

Solstice:

An Electronic Journal of Geography and Mathematics, |

|

Congratulations to all Solstice contributors. |

| Remembering

those who

are gone now but who contributed in various ways to Solstice

or to IMaGe

projects, directly or indirectly, during the first 25 years of IMaGe: Allen K. Philbrick | Donald F. Lach | Frank Harary | William D. Drake | H. S. M. Coxeter | Saunders Mac Lane | Chauncy D. Harris | Norton S. Ginsburg | Sylvia L. Thrupp | Arthur L. Loeb | George Kish | |